Human Nature Perfectly: An interview with Travis LeRoy Southworth

by Amanda Nedham & Kyle Hitmeier, 03.21.2021

From the exhibition Human Nature Perfectly, Below Grand NYC

For Below Grand NYC (formally Super Dutchess) virtual show, “Human Nature Perfectly” Amanda Nedham and Kyle Hitmeier interviewed artist Travis LeRoy Southworth to talk more about the artist’s work and practice.

BG: Your recent new body of work, ‘Familiar Faces,’ is a slight departure from your earlier work, contextualizing your process within the confines of a pandemic. As a professional in the photo retouching industry, how do you reconcile this newfound engagement with touch and intimacy, or lack thereof, among your subjects? And can you speak specifically to the tension in your work between familiarity and alienation?

TLS: I spend a lot of time thinking about touch, both bodily between two people and through computerized devices. There can be an intense level of intimacy and contact in both but from there they veer in different directions. For example a soft physical caress versus a quick digital swipe; one has texture, warmth, give and take; the other is smooth, singular, uncaring, and sometimes violent.

I often half joke that we touch screens more than the ones we love. It is ever on my mind as I spend a large portion of my time in front of a computer both as a photo retoucher and an artist. Much of my practice involves stockpiling hidden aspects of production such as blemishes, color adjustments and digital masks to construct new portraits.

For myself, living in New Jersey and working in New York I am relatively close to people on a daily basis. When the lockdowns began as a result of the pandemic it had a jarring effect. This not only was because of the lack of bodily presence but because people I was familiar with became strange and unrecognizable due to masks, limited interactions and an absence of response.

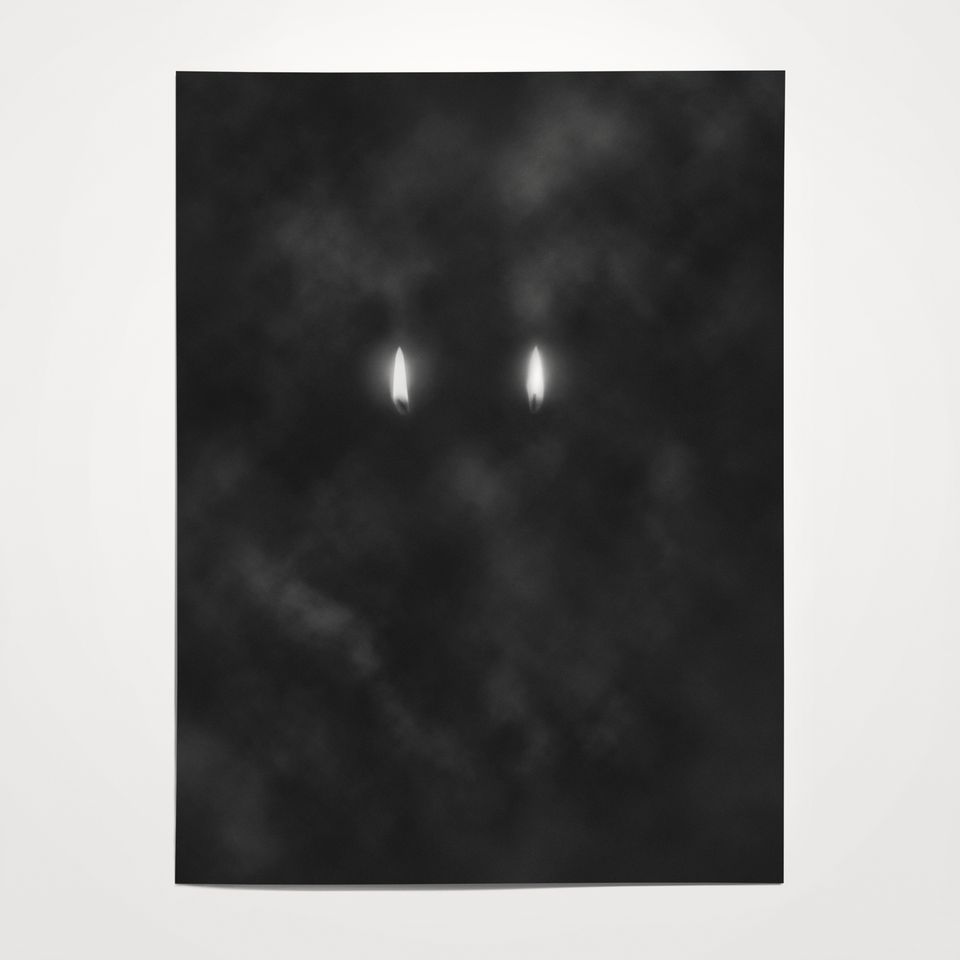

The process of retouching can be a meditative act and I sometimes work through ideas in my head as I push pixels on a computer screen in a darkened room. It made me think of the digital masks I use to conceal body parts or add color to an image while working in Photoshop. The masks are represented in complete black and white to show the area of the image and how much it has been exposed to the current adjustment. I especially liked how the masks looked for portraits where I had to darken or lighten an area of someone’s face. It became sort of a quick sketch of a partial face. Something recognizable but at the same time not human.

These gestures became the jumping off point for my new work ‘Familiar Faces’. Acting as a base layer I create additional black and white color fills and paint through masks to create my works. I replicate elements of the process in my work which creates even more masks which in turn creates families or relatives of works in their own right. I thought of the many interactions between people I’ve had during the pandemic and wanted to depict those feelings and moments and not necessarily specific people. The new works definitely have a stronger connection to personal experiences that I feel translate to a larger audience than my past work. I see ideas of familiarity and alienation shifting for me in a weird way.

BG: At times the masking along with the black and white processes gesture toward the cartoon in that some of the hardline contours you’re including carve a definition into the figures that define their ghostly underlayers. Historically, cartoons have been versatile rubrics that can fold in socio-political context. Do you feel that you’re intentionally creating commentary? Or does the presence of auras say more about human nature in general?

TLS: I have been thinking a lot about the history of cartoons and there are some overlapping constructs. The word cartoon is connected to caricature, which is derived from the Italian caricare, meaning to load or imply exaggeration. Cartoon came from cartone, referring to the heavy paper which artists in the 1670s used to sketch out their works. While examples of caricature existed in ancient Egypt and Greece, some historians also consider the cave paintings in southern Europe from 30,000 years ago to be some of the first cartoons due to a sense of exaggeration, movement and fun. Political caricatures became popular in the 1700s in Italy and later in the 1800s in England and the United States. It was around the mid-1800s that the word cartoon began to take over. Satirical political cartoons often boom during times of revolution and unrest.

Since my series ‘Familiar Faces’ is ingrained in my response to the pandemic I would say it does use some aspects of caricatures. I want to create a space where the viewer could see themselves in the work or a situation they have experienced. As I shape my fictional portraits there is an implied movement in my works obtained through the soft sketch-like quality. I wouldn’t say they have hardline contours but I do see what you mean as some works can appear stark from the use of tonal range. I use very low opacity brushes in Photoshop to slowly build up works and maintain a glow or atmospheric impression. I wanted to remove the division between figure and ground and create an environment where one blends into the other. There is a flow among the work, some pieces appear more menacing and subtle while others humorous and recognizable.

BG: Along with that starkness, there is a dramatic shift of scale within the works. You blur the boundaries between what is uncomfortably close and comfortably far through the evocation of both the petri dish and the agreed upon social distance regulations of the pandemic. In regard to the installation series in the Super Dutchess virtual exhibition, ‘Human Nature Perfectly,’ how do you consider the co-mingling mass of figures, and what role does scale play in this?

TLS: When I saw the Super Dutchess gallery I was immediately struck that its unique size is nearly the same six-foot distance people are supposed to maintain from one another during the pandemic. Thinking about this, it looked like a container that could comfortably fit one person but could also hold twenty people if crammed together. It connected with the ideas of containment and separation perfectly in work I am making. The glass doors act as reflector to not only the work but to visitors as well.

When working on the pieces in my studio I found that certain works appeared to be ‘looking’ at others and I started playing with that. Relationships between artworks began to develop. The salon style hanging adds a level of connectedness within the work itself but also gives additional movement. Like you said, they start to form a mass or even a crowd. I think about distance and the perception of depth a lot in my work. I want the audience to see the work from afar but to get really close as well. I think how ‘Familiar Faces’ is displayed in SD can get at this.

BG: We are approaching the one year anniversary of the pandemic and are beginning to see the light at the end of the tunnel, but will be processing everything that has happened for a long time to come. Cultural institutions have been grappling with how to respond to both Covid-19 and BLM, as we continue to cope with loss. The digital space has become even more human as we use the same platforms to fight for justice and check in with loved ones. What does it mean to embark on a virtual exhibition at this moment and do you see the digital space differently than you did one year ago?

TLS: It certainly has been a difficult year all around. Many of us have been struggling financially, dealing with loss and trying to pull our lives back together. For artists we have had to redefine what it means to both make and exhibit art during a pandemic. Those of us who have presented work to exist as online exhibitions, there is that awareness of trying to get beyond rendered artworks placed into a digitized gallery.

As someone who works in conceptual series I often think about presentation as I create each piece. While there is a long history of artworks made to exist online, for the first time there is a larger audience for virtual exhibitions. So much has accelerated in the last few years as digital environments alone have gone from obviously rendered to lifelike. Technologies such as augmented and virtual reality are offering more flexibility in ways art can be viewed. And things like Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) through Blockchain are allowing artists to sell digital work and extend their practice. The inability to be physically present and view art in the last year has certainly increased the appeal of virtual exhibitions.

The challenge now as I mentioned previously is to play to the strengths of digital and move past the white cube. Make the exhibition an artwork in itself, a unique experience that otherwise would not be able to be experienced in the same way physically.