Scratching The Surface: An Interview with Travis LeRoy Southworth

by Breezy Art, 01.21.21

This interview started with the intention and the distinct pleasure of sharing thoughts with the artist Travis LeRoy Southworth and letting him take me through the path of his art and life.

I entered the universe of Travis a few years ago, when I found myself lost in a “perfect” world existing in imperfection. Working by day as an image correction specialist in the beauty industry and spending hours removing moles and imperfections, the artist chooses to keep the pixels of what the social conventions of appearance refuse and hide. He doesn’t throw away what society is somehow unhappy to see, instead he keeps all these “flaws” and he integrates them into his work, creating new portraits and opening up discussions of image manipulation, computerized labor and self-perception. For the past seventeen years, he has dedicated his life to visualizing the unseen. And today, for an ironic twist of fate, his personal life and his artistic practice walk closer than ever before.

This interview didn’t take place in just a few hours nor one day; it was a “route” that the artist and I traced together while waiting to see what the next step of the discussion would be. Hopefully you will read through it and you will take part in the journey.

- Eleonora Brizi -

EB: A main focus in your work is imperfection, both in the body, and as a cultural obsession. Body flaws become precious and unique, and even the medium for your work. The blemishes the beauty industry deems unfit for reproduction are a big part of your work, but I'm wondering if you could begin by talking about your relationship with your own imperfections?

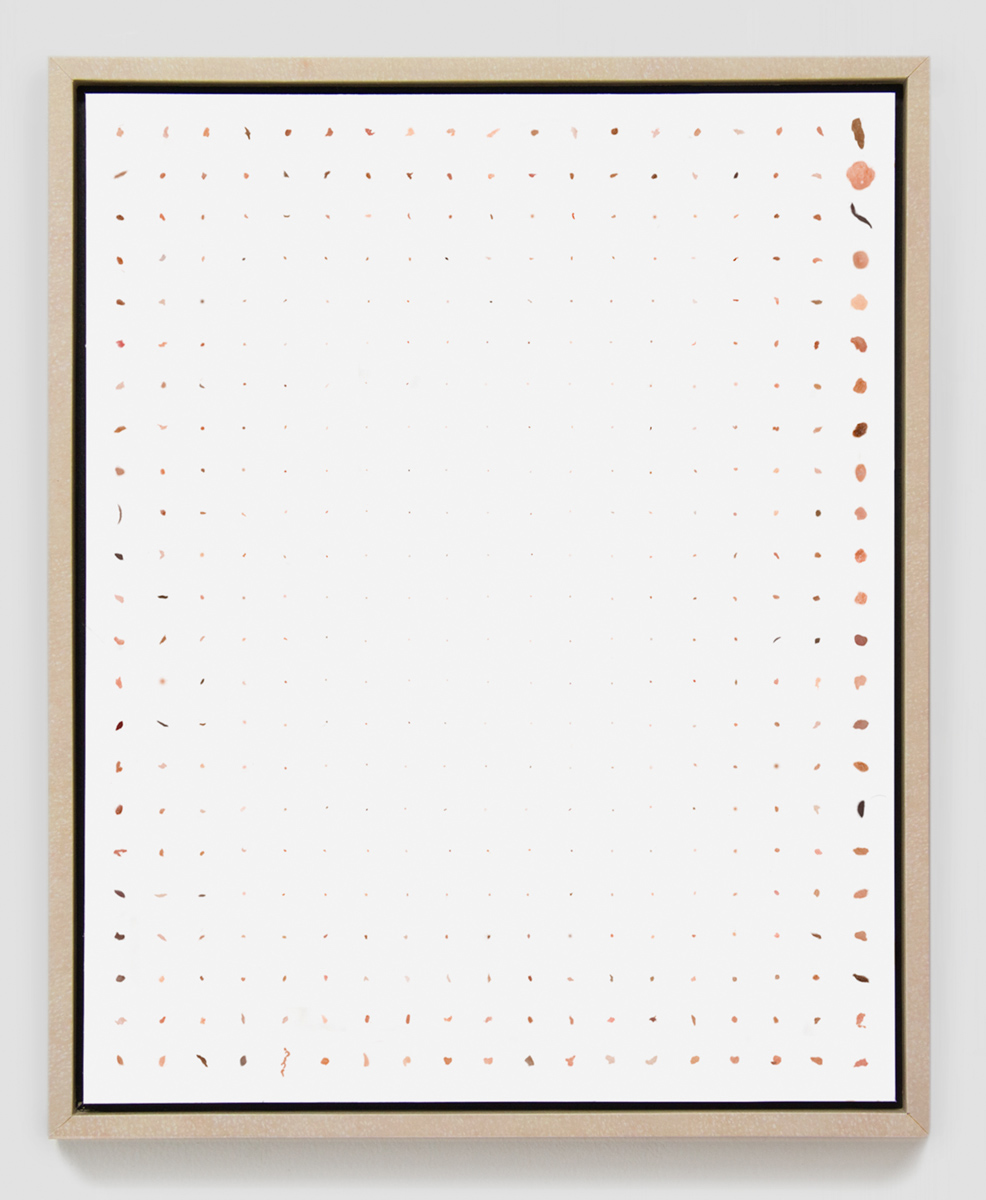

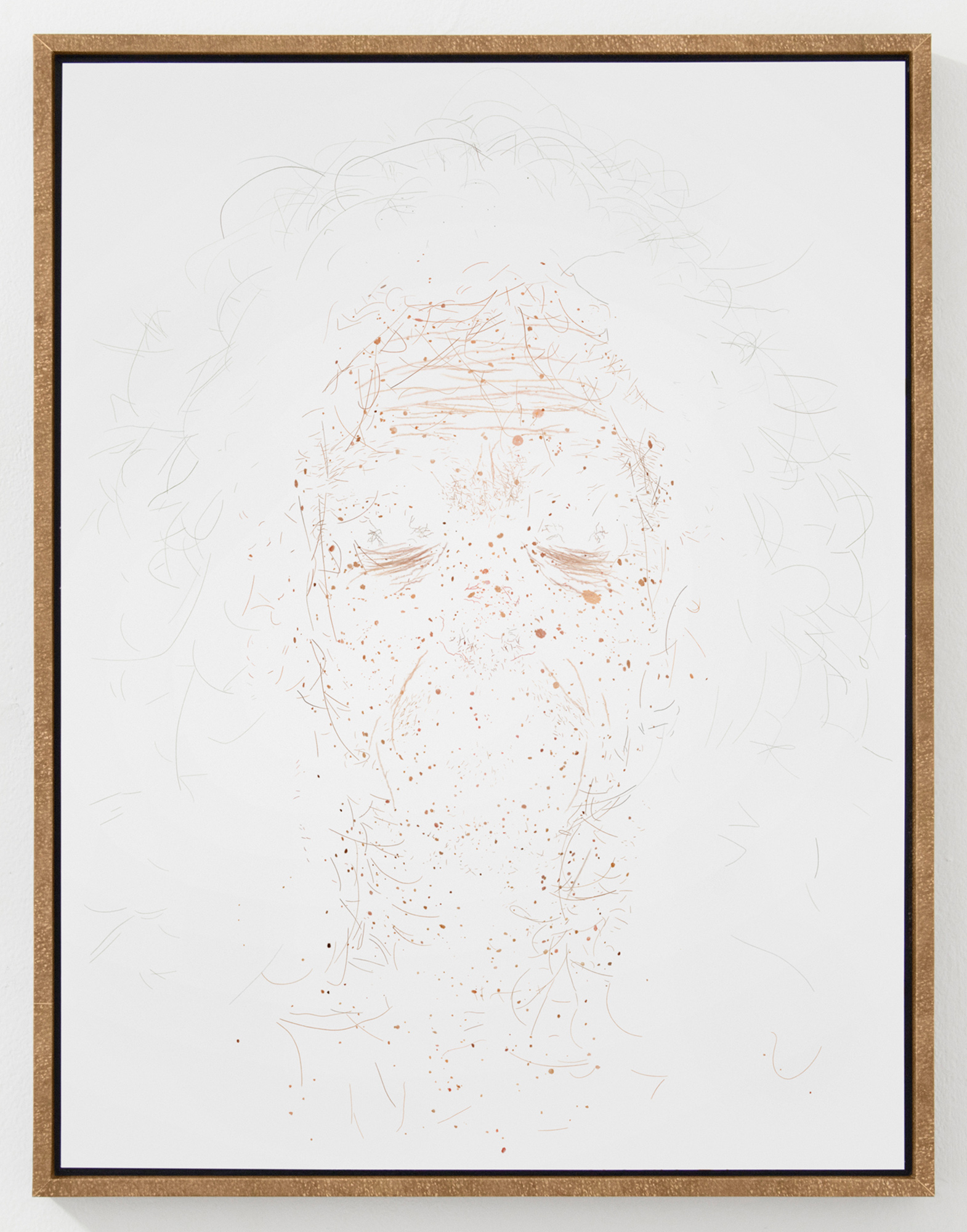

TLS: I use technology to both expose and detach myself from the construction of beauty standards online. I thought if I was going to subject people to an extreme examination of their physical ‘flaws’, I should start with my own. One of the first pieces I made in this style was a self-portrait titled I Re-touch Myself, 2007, where I erased my entire face except for the imperfections. As someone who has numerous moles, freckles, wrinkles and small scars it became quite an undertaking zooming in and digitally removing each one of those. This type of intense scrutiny can feel invasive for people. By starting with my blemishes, it was a way to expose myself and too see what a vulnerable male body might look like. The process of retouching my likeness was oddly meditating yet unsettling. It became a weird metaphysical moment to stare at my face so close on a screen for hours on end.My art practice focuses on the ways technology can distort body image. The exposure of the first piece is part of the work, making what is hidden visible. My series Detouched, 2007-15 dealt more directly with facial ‘flaws’ and was partially born from my professional work as a photo retoucher. I became interested in all the tiny imperfections that I had to remove from photographic portraits. I saw these ‘bits’ as the things that make us unique from one another. So I started erasing entire faces in Photoshop and only leaving the supposed rejected elements. In doing so, I created abstract portraits of people’s unique markers. From a distance they looked like dots on a white piece of paper; possibly inverse images of the cosmos. But upon closer examination, small details of skin revealed bodily origins.

Looking back at that first artwork from thirteen years ago I never thought that my work would continue on this path. In November I learned that one of my facial moles had turned malignant. While the diagnosis adds an auspicious layer of meaning to my work—blemishes can kill—I would prefer if these layers didn't have to come from the personal experience of skin cancer.

EB: Your video Absent Minded Monotonous Splendor, 2010 pairs a monologue on the Big Bang from the TV series The Universe with a portrait of yourself where an unknown force slowly erases your face until all that remains are the moles. The remaining imperfections explode and form a new solar system. Today, this piece that was already so powerful, becomes even stronger. Can you talk about what you were thinking about when you made this piece? Why does the portrait explode and why only imperfections stay? Is there a specific reason for which you have chosen yourself as the subject?

TLS: When I made that piece, I thought a lot about overlapping themes of creation, rejection, and reformation in this work. In a way I saw the explosion of my portrait as a destruction of the old me, both as an artist and a person. My imperfections represented things society deemed unfavorable but I thought had true value. From those I could become something else.

For me, the art making process is always an examination of yourself in relation to the rest of the world—a point reinforced by the appropriated voice over. “The big bang is...the ultimate creation of every story. We’ve pieced together a vision of the universe and made sense of it from science and discovered our place within it.” This led me to consider the unseen on a deeper level and think about how tiny fragments of the body connected to the particles that comprised the cosmos reveal our intrinsic connection to the universe. I feel the most interesting artists transform and reinvent their work over time.

The video takes the form of a pseudo Photoshop tutorial, showing the erasure of a face that then transforms into space. At the time I was also thinking about the growing circle of friends I made in New York who all worked in the art world. I decided to photograph them and include their imperfections in a series titled Where I End and You Begin. In a way it became an abstract representation of my expanding galaxy of acquaintances and people who made a mark on my life.

After 11 years, how has your relationship with the piece changed over time? It seems really relevant to your practice.

Definitely. Looking back, the piece became a distinct marker for my artistic practice. My work looks different now but the explorations of the body in relationship to digital mutability are there.

In many ways I relate to it in the same way as the portrait of myself as a young artist. It was me, but so many things have happened since that time. I recognize myself but it’s hard to believe I was ever in that space. Viewing it today, my younger likeness seems forever doomed to repeat cycles of erasure and transformation, never finding a suitable form. The video itself still feels fresh and my practice is shifting back to further examinations of skin and screens in a new series.

EB: Hearing the story of your art, it is fascinating to see how strongly related it is to your personal one. Can you talk about that connection?

TLS: I spend a great deal of time thinking about representation and what it means to depict an individual at a particular moment in time and space. I try to take the good and bad in my life and integrate it in my art. Turning 40 just over a year ago coupled with other chronic physical conditions has also primed me for the reality of aging. I spent much of my 30s in pain from a herniated disc, mild scoliosis and bone degeneration of the lumbar spine. I felt I hit middle age a decade earlier than most people. I still have to dedicate an hour or so to physical therapy each day to remain mobile. My wife Marta says I am a born Stoic. While I don’t tend to get deep into any particular belief structure, I agree with the summary of Stoicism on Wikipedia. "According to its teachings, as social beings, the path to happiness is found in accepting the moment as it presents itself, by not allowing oneself to be controlled by the desire for pleasure or by the fear of pain," It reads. Acceptance also comes "by using one's mind to understand the world...to do one's part in nature's plan, and by working together and treating others fairly and justly." I think the world could use a lot more of this, especially after witnessing the aftermath of what happened in the U.S. Capitol.

Prior to my diagnosis I was thinking a lot about social media and the negative effects it has on the body. Just the amount of time we spend in front of screens today is horrendous. We have such relationships with our devices that we touch screens more than the ones we love.

I’d like to go back to your most intimate story in relation to your work. You were diagnosed with skin cancer that is affecting your face: how does your art practice help you to get through it and vice-versa? How are you funneling the experience into your art?

I am sure the skin cancer will find its way into my artwork, I am already seeing tumors and abnormal shapes in recent paintings. I feel like much of our youth is focused on growth and transformation of the mind. There is this gray area somewhere between 30 and 40 where that stops and the body starts to reject the brain. Specifically with the cancer it felt like an about face and rebellion; telling me this is the beginning of the end.

EB: You consider the series of works named New beginnings, old endings, secrets secreting (2019-2020) more self-portraits that express your own fears and hopes than autonomous figures. How does it relate to what is happening to you and to the world right now? What technique did you use for these paintings?

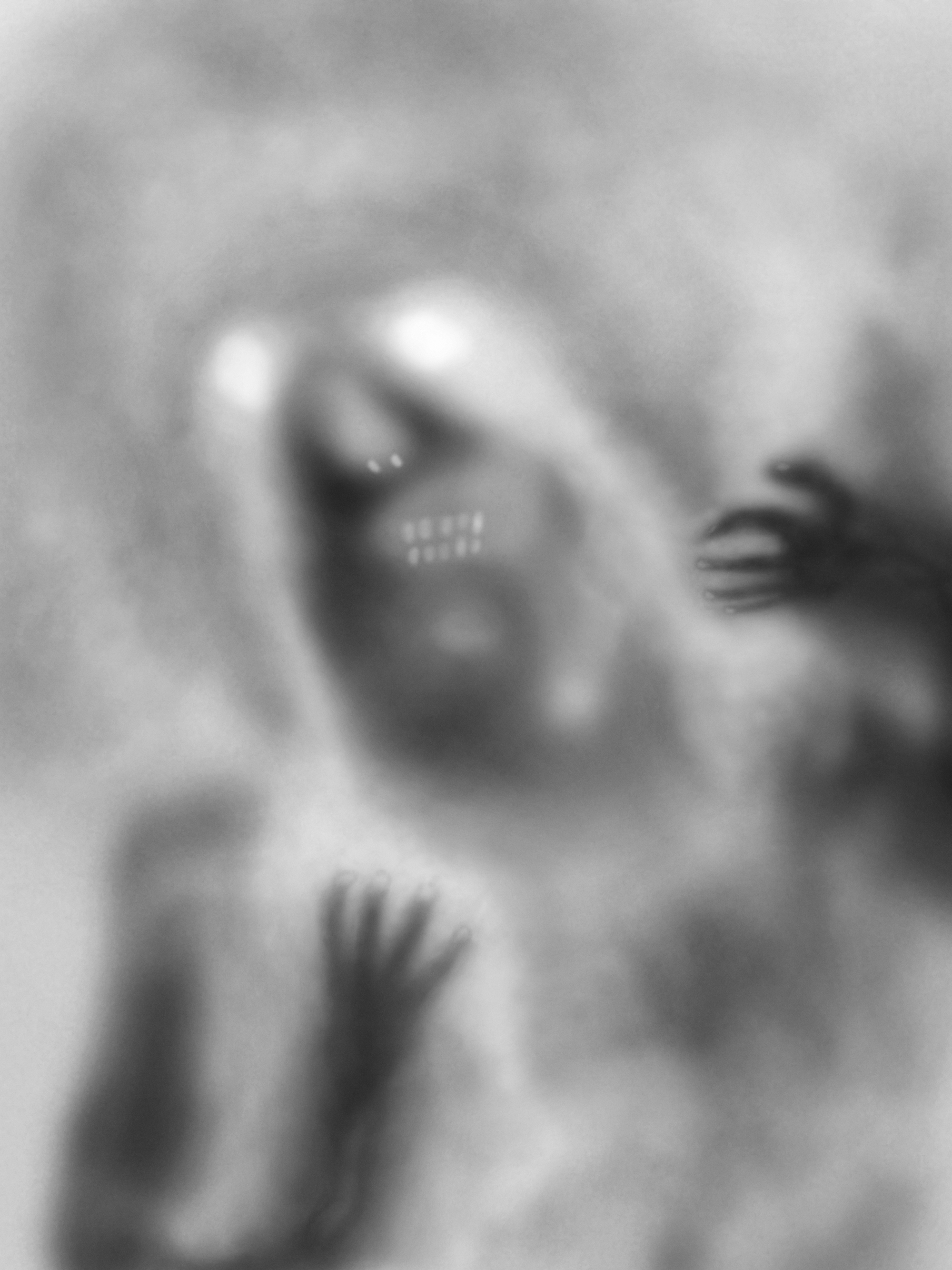

TLS: In 2018 I became interested in Machine Learning and how it could lead to image production changes in the advertising industry. I studied neural networks and toyed with using a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) as a potential artmaking tool. A GAN is basically a computer system where one network is given hundreds/thousands of images of something, say a cat, and learns what features make a cat look real. It provides feedback to another network that generates images of a cat based on the dataset of images it is given. This process can be repeated with the newly created images as it ‘learns’ how to make a photo-realistic image. My series New beginnings, old endings, secrets secreting uses my previous work from my paintings Color, Balance as a dataset to train a GAN and create images combined with specific portraits I found online. The computer created images act as a base layer for a painting I further work on in Photoshop. Currently I use Playform, a GAN available to artists who may not have the coding background to set up their own network.

AI has huge implications for artists and image editors. I find it fascinating that I can train a machine from a series of portraits to create images of people who never existed. Computer scientists often refer to early neural network images as ‘dreams’ due to their soft surreal-like quality. Considered a stepping stone in the search for artificial intelligence, hopes and fears surrounding these technologies attach themselves to ideas larger than any individual advance. The subject prompts consideration of my dreams and nightmares; real and imagined, small and large, wholesome, and vapid. I pair each work with a specific hope or fear of my own. These imbued feelings are bits of my unseen character and help shape each work.In many ways AI feels like an erasure of the self. Already, technology causes feelings of alienation, effacement and rising division come to mind. As artists, the medium can feel larger than our ability to wield it. No creative act can thwart the disconnect social technologies create. We can use the technology to bring attention to its effects, though, which is what I try to do with my work.

EB: You mentioned that the process of art making is a bit like studying and understanding our relationship to the world. We're surrounded by masks, both literal and digital and have “finally” hidden all our imperfections. But we all look the same—as if we have all got retouched in Photoshop. What remains? Familiar Facesis a series of quick gestural portraits in black and white that responds to Covid-19. Why this title?

TLS: I chose that title because during COVID I began to notice that even in my neighborhood, familiar faces began to appear strange. People became unrecognizable due to masks, more limited interactions and an absence of response. I started this work because the current moment resembles an urban fog from a dystopian novel, where faces appear distorted, and figures disappear into a colorless haze. I wanted to create portraits that were supposedly of someone familiar but now were transformed into something less recognizable.

I liken it to an article I remember reading in 2008 about the image manipulation of portraits titled Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: Enhancement in Self-Recognition. In it participants were asked to pick their actual photographic portrait out of a lineup of enhanced images, both made more and less attractive. As a whole people would overwhelmingly pick a more attractively altered image as their real representation. While I am glossing over a lot from the article, for me it foreshadowed a growing disconnect beginning with oneself and the acceptance of an alternate reality.The pandemic only quickened the pace of this disconnect. I wonder if we're entering a more selfish time. Has wearing a mask contributed to this? In a way the cloaking of one’s physical face now matches the mask that digital avatars have offered for years. This creates an additional rift in personal interactions along with extreme disagreements that involve the policing facial coverings. We're surrounded by mirrors that reflect our own image and those whose views align with our own, but no one else. Our views become less complicated and when exposed to other points of view, not only are we further apart in opinion, we have far less experience responding to it.

EB: Amongst the many lessons that we are learning from this pandemic, is the triumph of the couple “nature - technology”: the essence and the progress. Your art subject has always included nature: that of human beings and their bodies, these containers through which we face the existence and the perception of “reality”. What role does technology play in your art process and where do you foresee us going with that?

TLS: Technology changes us. At its best, it helps us construct buildings, cities, and machines that allow us to live easier and longer lives. At its worst it can help incite wars and end life in an instant. I do feel we are becoming less empathetic to one another. I wonder how much technology plays in this role. Have we lost empathy because the majority of interaction we have occurs online, and thus we are losing that human touch?My art practice engages the use of computer software as it removes all traces of my hand— the process iterates the body’s disappearance on and off the screen. With this work, I aim to express how 21st century identity is shaped and defined by a disconnect between the body and those around us. I have never been a big sharer in social media and the last few years have really created cultural, political and bodily divisions. My new project Screen Skin marks a critical turning point in my work, as I turn my focus to the real-world physical damage inflicted on the body by supposedly benign technology.

EB: You mentioned you are not big on sharing on social media. But somehow you chose to use the medium to reveal the news about the diagnosis of your skin cancer. Why?

TLS: I recently shared the news of my skin cancer on social media and wanted to include it in this interview because I wanted to publicly acknowledge its existence. I tend to be a private person and at first didn’t think I was going to tell anyone aside from immediate family and a couple friends. But doing so, for me felt like a way of erasing it all together, like it was never real. I’m glad I didn’t do that. Already, dozens of friends and acquaintances have reached out who went through similar situations. It helped immensely both to normalize it and also to have another individual to talk to, even if not in person. The distancing the pandemic requires affects our collective psyche; we need more human interaction than we get. While that may not be physically possible for everyone at this moment, it will be sometime in the near future.

EB: We started this interview a few weeks before your surgery. We paused during the crucial days of the procedure and we kept working on it even just right after it happened, as soon as you were able to. I felt our dialogue was very much alive and that this whole discussion was one of the most special I have ever had: we knew how it started but we had to follow to see how it would end. For this reason, we both felt the need and the beauty of including the story of the actual surgery.

TLS: Yes, we weren’t really sure where the interview would go, but after my surgical experience I had the strong desire to flesh it out (pun intended). A big part of that is rooted in the procedure itself, which involves the physical process of hiding or removing parts of the body. But I also felt like the surgery gave me a greater clarity on the relationship between the physical body and the digital presence and that seemed really important to share.

For someone who can barely stand putting anything close to their eyes, having incisions made within millimeters of the same area isn’t something I’d wish on anyone. But because my practice is rooted in closely examining faces both in an objective and artistic ways, I feel it’s important to describe the process.

I ended up having three surgeries in one day— two to remove the skin cancer and one to repair my face. I was awake during all procedures with a local anesthetic in the cancerous area. The Mohs surgery itself was quick, the most disturbing part was having my wound cauterized and the immediate smell entering my nose. The two hour wait between surgery and analysis was weirdly calming as I tried to further work on this interview. I only had to experience that twice as the doctor was able to remove all of the skin cancer after the second pass. I was then cauterized, bandaged and sent on my way to walk across town to my next appointment with the plastic surgeon. The walk probably took longer than the runtime of the actual procedures.

While the Mohs visit involved meeting several nurses and doctors, the reconstruction involved only the plastic surgeon and myself. I laid there again with coverings on my eyes and mouth. The doctor was quite talkative as he worked. With my skin numb I found it surprisingly easy to talk with limited movement. I imagined what the doctor saw and what I looked like, with only my nose exposed and cancerous skin removed. Both of us still wearing masks, mine just covering my mouth, we discussed a surprising number of topics in twenty minutes. I could hear the distinct sound of the scissors cutting through my skin and feel the pulling from his hand to stitch it together. We talked about having kids and gaining a layer of empathy through biology and the experience of protecting and raising a child who would not be able to exist on their own. In that moment of near complete bodily covering I allowed myself to be as vulnerable as a child. A stranger was taking care of me. I could not see them, and they, only a small part of me. It was surreal in that it felt normal.

EB: Thank you infinitely, Travis, for having shared this time with me; for telling us about your vulnerability and talking to us about your art. When the liable and thin border between what is personal and what is artistic in the life of an artist seems to be even blurrier, I was happy and grateful to be part of this great story of art and humanity.

TLS: Thank you Eleonora for working with me on this story. I can’t imagine a more thoughtful and caring person to discuss these ideas with.